With the April 2025 arrival of a new album “The Hemphill Stringtet Plays the Music of Julius Hemphill” (Out of Your Head Records), I have happily fallen down again the rabbit hole of re-listening to saxophonist and composer Julius Hemphill (1938-1995). I am amazed he’s been gone for so long because his music has been so much a part of my life as a listener and writer from the time I discovered “Dogon A.D.” in its first reissue in 1977. The whack of Phillip Wilson’s drums (Wilson who I knew from the Paul Butterfield Blue Band), the hard-edge of Bakaida Carroll’s trumpet, the blues bass lines of cellist Abdul Wadud, the sonorous low notes of baritone saxophonist Hamiett Bluiett, and the sweet alto saxophone of the leader, transformed my understanding of the Blues and how it permeates Creative Music.

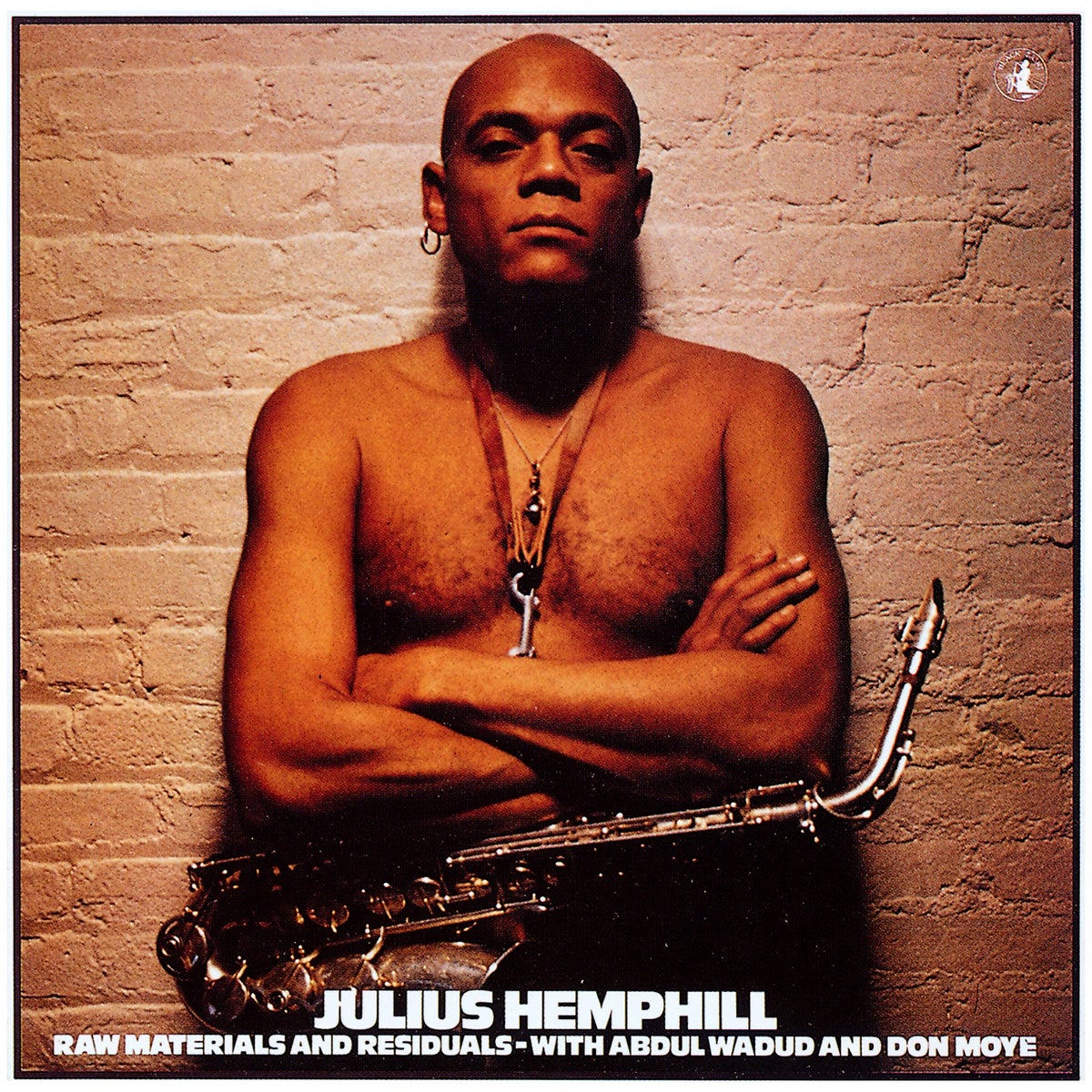

The 1970s was a great time for Black Music (not for sales and gig opportunities but in the landslide of great original music). The artists of Chicago’s AACM such as The Art Ensemble of Chicago, Muhal Richard Abrams, and Trio Air, made classic albums while Hemphill recorded numerous times for Italy’s Black Saint label, for Canada’s Sackville label, and on his own Mbari Music. His two conceptual solo albums, “Blue Boyé” and “Roi Boyé and The Gotham Minstrels”, are masterworks in creativity, multi-tracking, and performance.

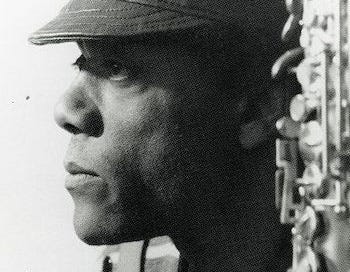

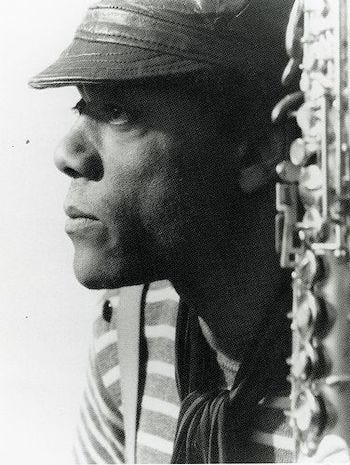

Around that time, Real Art Ways of Hartford, CT, begin a series of concerts bringing New York City-based artists such as saxophonist Arthur Blythe, violinist Leroy Jenkins, and others to play in its un-air-conditioned performance space across from the Hartford Civic Center. Hemphill, dressed like he is in the above photo, played a mesmerizing solo concert. I remember little of the music but we all sweated together in that room as the artist played his way through a series of pieces steeped in blues, swing, free-music, poetry, and Gospel wailing. I tried to interview Hemphill after the show but he was drained, covered in sweat, and needing to rest.

Several years later, my wife and I went to a venue near New York City for a concert headlined by the Art Ensemble and opened by the World Saxophone Quartet. WSQ––Hemphill, Oliver Lake, David Murray, and Hamiett Bluiett––strutted onstage in their black tuxedos and set the venue on fire. We stood for the majority of show as if commanded by the ensemble to shout in response to the glorious melodies and fiery solos. The AEC followed and lived up to their reputation as mercurial performers. They, too, could rock a house but not that night.

Hemphill roared into the 1980s with a slew of albums as a leader and with WSQ. When Nonesuch Records signed the quartet, the label also released an album by the Julius Hemphill Big Band. The recording gave the composer the opportunity to rework earlier pieces for a 15-piece ensemble and to experiment in many areas. He also created several new pieces that showcase his alto sax––one such composition, “For Billie”, stands as one of his most impressive works not only for the warm arrangement but also his great solo!

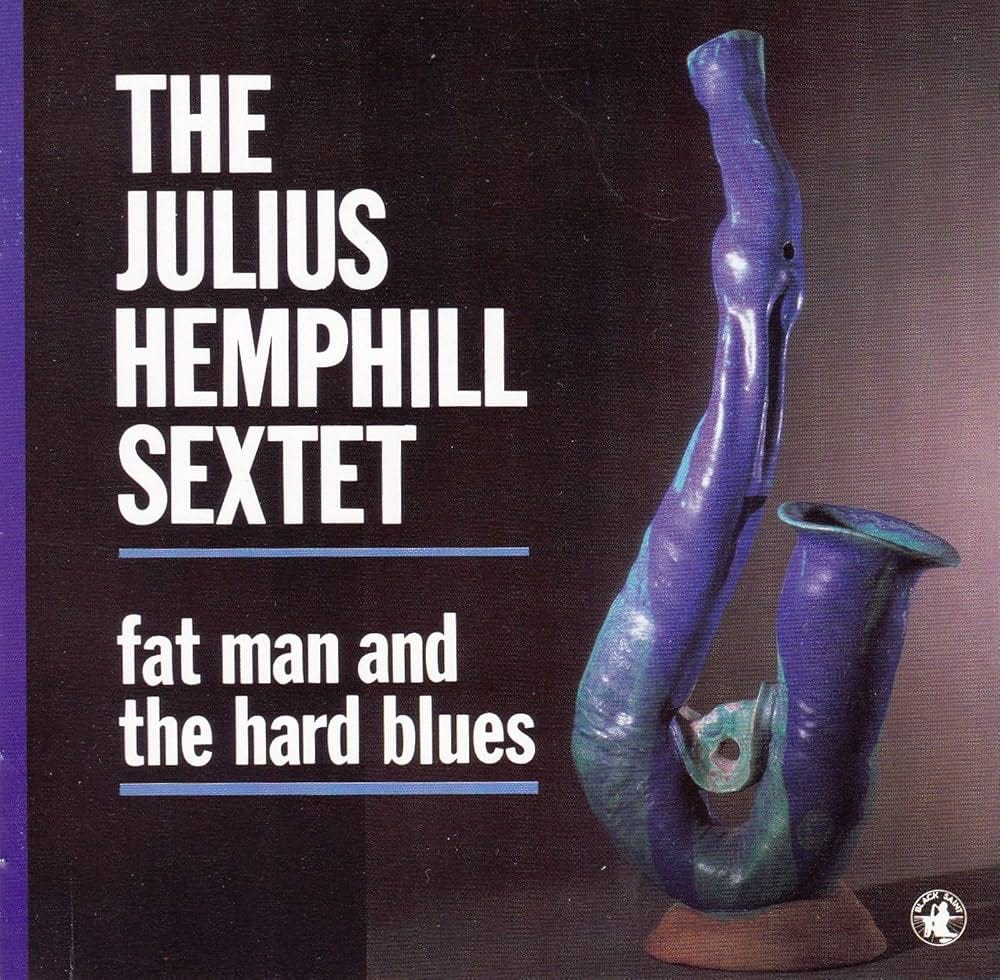

WSQ worked throughout the 1980s touring and recording three more albums for Nonesuch before Hemphill left the group. He then expanded his sights to create a sextet. He worked with the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zanes Dance Company to create the live soundtrack for Jones’ “Last Supper at Uncle Tom’s Cabin/The Promised Land” that premiered in November 1990 at The Brooklyn Academy of Music. In April of 1991, the show came to Wesleyan University in Middletown, CT. The Sextet played onstage as the dancers “told” the story. Dancers of all shapes, sizes, and ethnicities moved about gracefully as well as getting “down” to some of the more “gutbucket” pieces. The Sextet also produced two albums for Black Saint, the one pictured above and 1993’s “Five Chord Stud”.

In the early 1990s, Hemphill was diagnosed with diabetes and soon after had heart surgery. While he had no choice to stop playing his saxophone, he continued to write for the Sextet (who released two more albums after Hemphill’s death) as well as to expand his sights to works for solo piano and and for string ensemble. In 2003, eight years after his passing, Tzadik Records released “One Atmosphere”, an album with works for String Quartet, for wind ensemble, and a smaller mixed group.

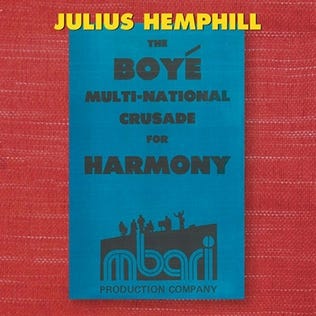

In February of 2021, New World Records released “The Boyé Multi-National Crusade for Harmony”, a seven-CD set of works that cover the full range of Hemphill’s oeuvre; from his solo music to duets with cellist Wadud and poet K. Curtis Lyle, to trio, quartet, string quartet, and sextet. Lovingly organized and curated by saxophonist and Sextet leader (after Hemphill’s passing) Marty Ehrlich, the set is stunning in what to reveals about the composer and the musician––he never stopped searching for new sounds. So much of his music is steeped in the blues (even the stunning arrangements of three Charles Mingus 1959 classic songs that serve as the centerpiece of the upcoming Hemphill Stringtet album); one also hears the influence of fellow Texas alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman and the improvisatory magic of Charlie Parker in his various projects. Not in his saxophone tone but in his ability to blur the borders of genres.

Julius Hemphill, like so many of the musicians and composers who came to prominence in the late 1960s and ‘70s, is an original. His music is different from contemporaries such as Wadada Leo Smith, Henry Threadgill, George Lewis, James Newton, Anthony Davis, even his compatriot in the WSQ, Oliver Lake. They share the distinction of being American composers, artists who illuminated the multi-faceted Black experience in its victories, hardships, losses, broken promises et al.

Here’s a taste of Julius Hemphill and Abdul Wadud from the 2021 compilation (no known recording date or location).

I’m unfamiliar with his work outside WSQ, but will now check out his catalog (the silver lining of Spotify’s dark evil cloud). Thanks!